Fully Awakened in Frog Pajamas.

My son’s preschool teachers once described how one of the principles of the play-based education that they practiced was to agree when the child picked up a square block and claimed it was a piece of pizza. The idea was to encourage the notion that there were shapes and forms that could be representative of other shapes and forms, because the neural pathways would ultimately allow the child to recognize that some peculiar combinations of straight lines and curves had specific sounds and meanings attached to them.

In other words: Letters and numbers. By agreeing that the building block was pizza you were setting the foundations of literacy.

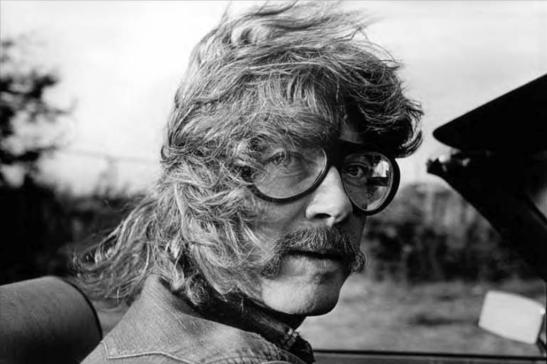

I don’t pretend to be the most passionate of Tom Robbins’ readers; although I did go through a period when his books were the only thing I checked out from the library and he’s still represented on my shelf by a 30 year-old copy of Still Life with Woodpecker.

There is, however, a passage of text that appeared in a random short story of his that I first read in college, titled Moonlight Whoopie Cushion Sonata, which I can and do often recite when I need to illustrate the possibilities of prose and the willingness to trust the audience’s imagination:

“The witch-girl sits by the bend in the river, sawing her cello with a bow made of human tibia, producing sounds like Stephen King’s nervous system caught in a mousetrap.”

(This is not exactly the sentence. I looked it up. But it’s not significantly different in my memory, and the effect of it is the same in either shape.)

On some subconscious level, I believe this sentence informed the next 20 odd years of my artistic life. It helped me stretch the boundaries of what text could do and helped me see objects in ways that I might not have otherwise. I doubt I would have done as well during my tenure within the Neo-Futurist ensemble without the neural pathways this sentence first pointed out for me.

So I do owe the man a measure of gratitude. And I wish him safe travels in whatever world he found beyond this one.