WRITE CLUB: LOOK

Write Club is a monthly, literary bloodsport in which contenders face off against each other with 7-minute essays on competing topics. Below was my combatant essay based on the prompt “LOOK,” facing off against “LEAP.” This essay was performed on February 20, 2024, at The GMan Tavern in Chicago. It was victorious in its bout.

There’s a passage of text I keep coming back to, over and over again, the way my dog will stare into the shadows under a tree where she might once have seen a snack-sized rabbit.

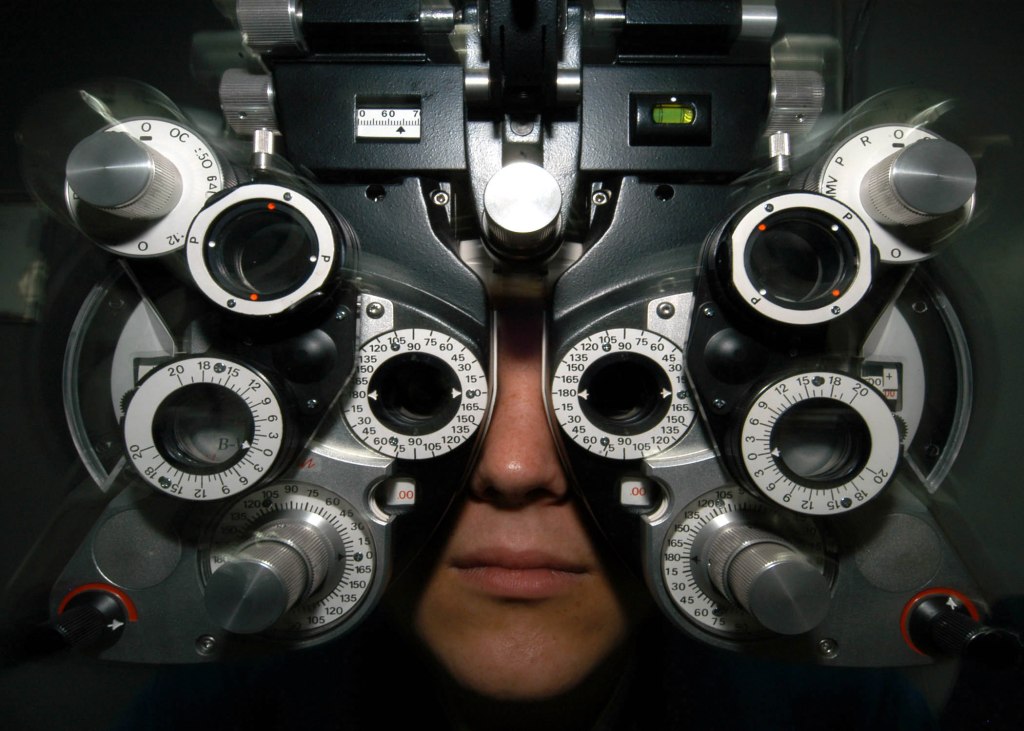

“The quicktank is given a job most of us would laugh out of town. Build a sophisticated camera capable of full 3-D input and peripheral pickup, using only water and jelly. Build an eye.”

The text is from a work of science fiction and I’m not going to burn my limited time up here going into the details of how a quicktank works or whether or not this description of a human eyeball is one hundred percent accurate. It’s a feat of poetic license and if you need to argue about it we can have Jill set aside a space at the bar so you can Facetime Dr. Neil DeGrasse Tyson and the cast of The Big Bang Theory and have the most obnoxious fucking conversation in the world about it. I keep coming back to this text not because I admire its science, but because I appreciate its sense of perspective.

An eye. We have built tools, industries, and social infrastructures around the relative miracle of this squishy, colorful globule rolling around in our skulls. We have written entire libraries of literature in veneration of individual sets of eyes, we have given ourselves lifetimes of nightmares about the trauma we could inflict upon them. They are painted on our churches and tombs, they are stitched into the backs of our currency. We do all this for these impossible hunks of water and jelly, and all they do for us is look.

But that’s not true, is it. We know better. We know that our eyes do so much more. They flash hot, they grow cold, they enthrall and seduce and terrify. We have come up with so many different words for what the eye can do, and your garden-variety thesaurus will try to sell you on the idea that many of these words are synonyms. But we are not reference books, you and I, we are living, breathing, magnificently sentient human beings and we know from our own experiences and behaviors that these are not the same.

A peek is not a glance. A glance is not a glimpse. A glimpse is not a scan. A scan is not a stare, a stare is not a gaze, a gaze is not a peer, a peer is not a watch, a watch is not an observe, an observe is not an examine, an examine is not an inspect, an inspect is not a study and a study is not a scrutinize. To look is not necessarily to see. To see is not necessarily to witness, and to witness is not necessarily to understand.

There’s a story I keep coming back to, over and over again, the way my dog will stare into the shadows under a tree where she might once have seen a snack-sized rabbit.

It’s September 26, 1983. In a military bunker near the city of Serpukhov, 100 kilometers south of Moscow, a lieutenant colonel by the name of Stanislav Petrov is monitoring the Soviet early warning system, with orders to notify his superiors if the Americans had launched nuclear missiles at them. This notification would then be followed by the launch of their own nuclear salvo, as required by the doctrine of mutually assured destruction, and everything that the world had been up until that point would be reduced to flaming cinder and regret.

After midnight on September 26, 1983, Stanislav Petrov receives a notification that there is a missile inbound. And for reasons that only he can fully understand, he hesitates. He considers the likelihood that an American nuclear attack would consist only of one missile, and when the missile fails to arrive he recognizes that the warning system has malfunctioned. And when the system warns him of four more missiles incoming, he gambles yet again that this is a malfunction. He refuses to believe that his counterparts would be so cynical as to end the world in this manner. He refuses to make that leap. He does not tell his superiors. The missiles do not arrive.

It’s September 26, 1983, and four days prior I turned six years old. I’m practicing penmanship and subtraction in my first grade class and utterly ignorant of how close I was to annihilation.

The Soviet missile warning system, incidentally, the one that failed so miserably it almost ended the world, was named око. Which is the Russian word for “eye.”

I am not someone who typically visits shrines or statuary. I believe there should be one or the other dedicated to Stanislav Petrov standing in every city that still exists because he thought better of his commands. Because he thought better of what he saw on his monitor, and decided instead to trust what he saw in people.

I think a great deal about the lesson worth learning from his inaction. I think about it every time I watch friends and family and complete strangers circulate unverified rumors and grammatically incorrect imagery still thick with the topsoil of the troll farm where it was grown. I think about a youth misspent looking for opportunities to attack people as a means to make myself feel powerful and why I have found myself much more inclined of late to leave my mouth shut while I keep my eyes open.

There’s a sentence I keep coming back to, over and over again, in which I describe my dog staring into the shadows under a tree where she might once have seen a snack-sized rabbit.

And I ask myself why she does this. She’s in many ways a very smart and perceptive dog, and surely she can tell there’s not a rabbit there now, and after four years of going on walks with me she can’t expect I would let her loose to catch it even if it was there at all. The rational part of me understands perfectly that the key component here is her prey drive. The rational part of me remembers that she’s probably not even using her eyes, that the most perceptive part of a dog is its nose.

The romantic part of me, the part of me I listen to when I don’t actually need a rational answer, that part tells me that this is hope. That the act of looking, however you look, with your eyes or without, that is an act of hope. Choosing to take in information and accept what the information is telling you but then also to take the moment to interpret it with generosity is an act of hope. The act of forming a perspective at all in a world so full of disappointment is to believe on some level that there may also still be something worth perceiving.

Maybe not right now. But eventually. If you keep looking.